Panaeolus cyanescens, often referred to as Copelandia cyanescens or just Pan cyan, is a small but incredibly potent mushroom found in tropical and subtropical regions around the world. While it shares the nickname “Blue Meanies” with some Psilocybe cubensis strains, Panaeolus cyanescens is in a league of its own when it comes to potency and characteristics.

Because of its long history under a different name, you’ll often see it called Copelandia in older books, forums, and even spore catalogs. Copelandia was originally treated as a separate genus, but recent genetic and morphological studies revealed it fits more accurately as a subgenus within Panaeolus. As a result, species like Copelandia cyanescens are now referred to as Panaeolus cyanescens — or more precisely, Panaeolus subgen. Copelandia cyanescens. While the name shift caused some confusion in the mycology community, it’s still the same species, just reclassified to reflect a better understanding of its evolutionary lineage.

In this guide, I’ll share my research and experience on what makes this species so special. We’ll explore everything from its unique identifying features and natural habitat to its chemical composition and current scientific findings. Whether you’re a researcher, hobby cultivator, or just curious about this species, you’ll discover what makes Pans unique compared to their more commonly known relatives.

Taxonomy and Nomenclature

The Panaeolus Genus

Let’s start with some context. The Panaeolus genus includes 114 recognized species of small to medium-sized mushrooms. What unites them? They’re typically saprobic, meaning they feed on decaying organic matter, and many show a preference for dung-rich environments. They’re also known for producing dark brown to jet-black spore prints, a trait that makes them easier to identify in the wild.

What makes Panaeolus cyanescens particularly interesting is that it belongs to a select group of psychoactive mushrooms within the genus. Of the 114 Panaeolus species, only 13 are confirmed (or strongly suspected), to contain psilocybin.

Psilocybin Containing Panaeolus Species:

- Panaeolus cyanescens (syn. Copelandia cyanescens)

- Panaeolus tropicalis

- Panaeolus cambodginiensis

- Panaeolus bisporus

- Panaeolus olivaceus

- Panaeolus subbalteatus (often reclassified as Panaeolus cinctulus)

- Panaeolus cinctulus

- Panaeolus acuminatus

- Panaeolus fimicola

- Panaeolus africanus

- Panaeolus antillarum var. cyanescens (very rare, and controversial)

- Panaeolus affinis

- Panaeolus papilionaceus var. parvisporus (some suspect activity; limited chemical analysis)

From Copelandia to Panaeolus

The reclassification of this species is a good example of how scientific understanding evolves over time. It was originally described as Copelandia cyanescens, but microscopic observations, and later genetic studies, showed it belonged in the Panaeolus genus. Mycologist Rolf Singer formalized the change, building on earlier work by Saccardo and others who had been studying these mushrooms for decades.

Pier Andrea Saccardo first described Panaeolus cyanescens in 1887 in his seminal work Sylloge Fungorum, laying the groundwork for future taxonomic studies. Singer later reclassified the species under Panaeolus, consolidating its taxonomy based on morphological traits. You can view the GBIF entry here.

For a quick overview of the genus and its naming history, the Wikipedia article on Copelandia gives a helpful summary.

Current Classification

Understanding where P. cyanescens fits in the fungal kingdom helps us see how it relates to other species. Here’s how it’s currently classified, based on what researchers have uncovered so far:

- Kingdom: Fungi

- Phylum: Basidiomycota

- Class: Agaricomycetes

- Order: Agaricales

- Family: Bolbitiaceae (sometimes Psathyrellaceae, depending on the source)

- Genus: Panaeolus

- Species: Panaeolus cyanescens

How to Identify Panaeolus cyanescens

Accurately identifying Panaeolus cyanescens is important. Not just because they’re potent, but because they share their habitat with other little brown mushrooms (LBMs), including some toxic species from genera like Conocybe and Galerina.

Macroscopic Features

Cap

Caps are typically small, ranging from 1.5 to 4 cm wide. They start out conical or bell-shaped and become broadly convex or nearly flat as they mature. Colors range from a pale, off-white to a chestnut brown, often drying to a yellowish or tan hue due to their hygrophanous nature. The surface is smooth and may crack in dry conditions and most notably, bruise a beautiful deep blue when handled.

Gills

Gills are closely spaced and attached to the stem, either adnate (square) or slightly adnexed. They start off pale grey and darken to black as the spores develop, often creating a mottled appearance due to uneven spore maturation.

Stem

Stems are slender, typically 5 to 12 cm long and 2 to 4 mm thick. Colors range from off-white to light grey or yellowish, often with a slightly powdery surface texture. They lack a ring (annulus), which sets them apart from some other species in the Panaeolus genus like cinctulus and subbalteatus. However, you will notice the characteristic blue bruising when handled, often even more dramatic than what you see on the cap.

Spore Print

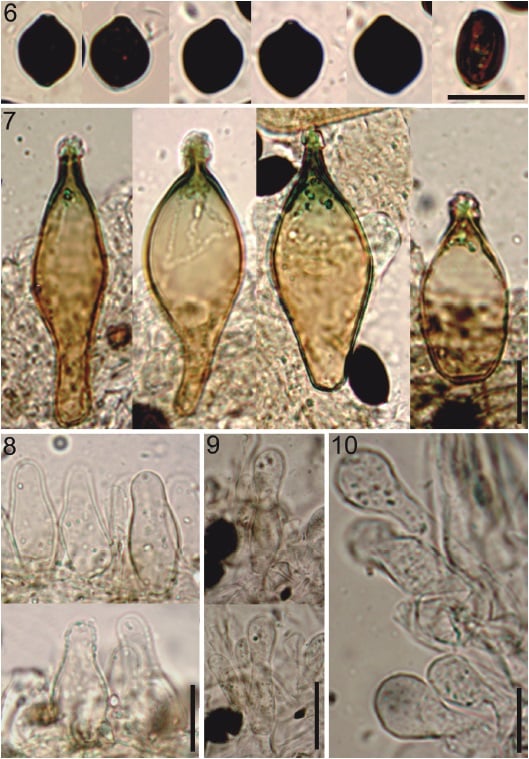

One of the most reliable field identifiers is the spore print. Panaeolus cyanescens produces a deep, jet-black spore print, often with mesmerizing radial symmetry. This helps distinguish them from species like Psilocybe cubensis, whose spore prints are typically larger, heavier and purple-brown in color.

Microscopic Features and Unique Characteristics

Panaeolus cyanescens have smooth, lemon-shaped (ellipsoid) spores, typically measuring 11–16 × 7–11 µm. The presence of specialized cells like cheilocystidia and pleurocystidia on the gill edges and faces are also key diagnostic features used in formal identification.

Distinctive Blue Bruising

One of the first and most obvious clues to identifying Panaeolus cyanescens is the intense blue bruising that appears when they are handled or damaged. This reaction is caused by the oxidation of psilocin, one of its primary active compounds. Compared to Psilocybe cubensis, the bluing in P. cyanescens tends to be darker and show up more quickly.

Phenotypes and Genetic Expressions

Although wild Panaeolus cyanescens tend to follow a fairly consistent morphology, cultivated varieties show a surprising range of variation. At first, I wondered if these differences might represent distinct species, but after working with the same cultures again and again, it became clear they behaved more like inherited traits – similar to how eye color expresses itself in humans.

While environmental factors can definitely influence appearance, these core phenotypes remain consistent across various cultures and conditions. Each one not only looks different but responds differently to its environment, so it’s helpful to recognize them early on so you can adjust your growing conditions accordingly.

Thick and Moody

This phenotype has noticeably thicker stems and caps. They’re often average or shorter in height, and sometimes have protruding gills. While they tolerate the lower end of the temperature range better than other phenotypes, they don’t handle heavy, wet, or stagnant air well. When things get too humid or the air isn’t moving, they start growing twisted and contorted.

When this phenotype shows up, it’s best to:

- Keep them out of your humidifier’s direct path

- Make sure there’s proper ventilation and steady air circulation

- Keep the substrate moist, but let the surrounding air stay light and breathable

Thin and Delicate

This phenotype produces tall, slender, elegant fruit, often with slightly smaller caps. They thrive in warmer conditions and can handle short bouts of stale air, but tend to abort quickly if the temperature or humidity drops too low. They produce beautiful flushes, but only if their conditions stay within a narrow sweet spot.

When this phenotype shows up, it’s best to:

- Keep temperature above 78°F (25.5C)

- Make sure temp and RH swings are gentle, especially if using an exhaust fan

Average and Undemanding

This phenotype is right in the middle and my favorite to work with. They have a hearty yet balanced look to them and often show a bit more personality than the others such as ruffled caps or candy cane-striped stems. They’re the most adaptable of the three and can handle both ends of the temp and humidity scale with ease.

Red Spore

One of the most eye catching morphological traits I’ve seen in Panaeolus cultures is the appearance of red gills and spores. Although rare, once expressed, this trait tends to stabilize quickly, often within just one or two generations. In my experience, crossing a red spore culture with another strain usually leads to offspring that also express red gills and spores within a few generations, suggesting it may be a dominant genetic trait.

This expression has shown up in several Panaeolus varieties, including Blue Springs, FL (Red Spore), PHV, and MIB. It’s a beautiful phenotype too. The caps and stems are generally lighter in color, which creates a stunning contrast against their vibrant orange gills. As the mushrooms mature, the gills deepen into a rich, rusty red. Fresh spores often display a deep red halo effect too, though this becomes less noticeable once they’ve fully dried.

Sterile Cultures

Another interesting phenomenon in Panaeolus cultivation is the occurrence of sterile mushrooms, similar to what’s seen with cubensis. While extreme humidity can impact spore development, some cultures seem to be sterile purely for genetic reasons. In these cases, it typically requires returning back to the print and establishing a fresh culture in order to get spores.

Identifying and Classifying Panaeolus Cyanescens

Mushroom identification is an ongoing process, especially in the Panaeolus genus. New species are being discovered regularly, and it’s people like you who are doing the research, making the observations, and submitting the data that help grow this body of knowledge.

South Africa is a perfect example of this. Back in 2022, a collection of mushrooms was found on the African coast that was initially identified as Panaeolus cyanescens. Genetic sequencing, however, suggested it may actually be a species all its own, similar to how Psilocybe natalensis and Psilocybe ochraceocentrata were eventually separated from cubensis. I couldn’t find any follow up data on this collection so I’m not sure what happened there and if they were ever properly identified.

The Panaeolus varieties known as “Weza” and “South Africa Mystery” may also be misidentified. It’s difficult to know for sure, since much of the data in GenBank is outdated, incomplete, or incorrectly labeled. Fresh, reliable sequencing is needed so if you’re interested in contributing, here are some resources.

Platforms for identification and research:

- GenBank (for genetic sequences)

- Mushroom Observer (for image-based observations)

- iNaturalist (for mapping wild finds)

- MycoBank (for taxonomic references)

- Index Fungorum (for classification status and synonyms)

Where Panaeolus cyanescens Grows

This species has a classic pantropical distribution, showing up in warm, humid regions across multiple continents. While environmental conditions vary slightly, it consistently thrives in dung-rich grasslands and pastures.

Geographic Distribution

Asia-Pacific

- Thailand

- Indonesia

- India

- Philippines

Americas

- Southern U.S. (especially Florida, Texas, and Hawaii)

- Mexico

- Central America

- Caribbean

- South America

Africa

- Along tropical and subtropical coasts and inland grazing areas

Australia & Oceania

- Northern Australia and nearby islands

Southern Europe

- Occasionally spotted in warm microclimates with consistent humidity

They tend to appear after seasonal rains or during periods of sustained humidity, often fruiting a few days after storms when the air is still warm and moist but the ground has started to dry slightly. In tropical regions, they’re most abundant during the rainy season, especially in the early morning hours when conditions are just right. Even small shifts in temperature, sunlight, or moisture levels can influence how often they appear and how long they last in a given spot.

You can view global occurrence data for Panaeolus cyanescens on GBIF.

Preferred Environment

Panaeolus cyanescens is a textbook example of a coprophilous mushroom. It thrives on the dung of grass-grazing animals, primarily cows and water buffalo, but has also been found fruiting on horse, elephant, and even hippopotamus manure.

In nature, you’re most likely to find them in:

- Open pastures and grazing fields

- On or near manure a few days after rainfall

- Grasslands with consistently warm temperatures and high humidity

Unlike some species that can adapt to wood chips, compost, or other plant-based substrates, P. cyanescens largely prefers dung. That preference can be a helpful clue when identifying them in nature.

Alkaloid Content and Chemical Profile

The primary allure of Panaeolus cyanescens isn’t just its potency, but the quality of experience it’s known to produce. That effect comes down to its alkaloid profile, and the unique proportions and ratios those compounds tend to show up in.

Key Psychoactive Compounds

Like other magic mushrooms, the effects come mainly from psilocybin and psilocin, with psilocin often dominating the profile. That’s worth noting because psilocin doesn’t need to be converted by the body like psilocybin does so the effects can come on faster and feel more intense.

Some research also shows trace amounts of baeocystin, serotonin, and other tryptamine compounds. It’s still unclear how much they influence the overall experience, but they’re part of the profile and likely contribute to why Pan cyans feel cleaner, lighter and more uplifting than other species.

Potency Levels

This is where Panaeolus cyanescens really stands out. Lab tests consistently show 2-3x times more active compounds than Psilocybe cubensis. Some samples have tested as high as 2% total alkaloids by dry weight, which is wild for a natural mushroom.

Of course, potency can vary based on genetics, substrate, and how the mushrooms are dried and stored, but even at the low end, they’re impressively potent.

Cultural Use & History

When it comes to the ceremonial use of magic mushrooms, most of the attention has gone to Psilocybe species, especially mexicana, zapotecorum, and cubensis. These are well documented in the rituals of Indigenous groups throughout Mexico and Central America, often used for spiritual healing and connecting with the divine.

Panaeolus species, on the other hand, don’t have that same recorded history. Despite the fact that species like Panaeolus cyanescens are significantly more potent than cubensis and produce what many describe as a cleaner, deeper experience, there’s almost no evidence of them being used in traditional ceremonies.

There are a few theories about why. Some cultures may have simply considered them toxic or unfamiliar, especially since many Panaeolus species grow directly on dung. Others may have used them but didn’t distinguish between genera, meaning any cultural knowledge may have been misattributed to Psilocybe. There’s also the fact that early researchers focused heavily on Mazatec and Mixtec traditions where Psilocybe got the spotlight, so it’s possible the use of Panaeolus was overlooked, misidentified, or just never written down.

One example of this confusion is Panaeolus sphinctrinus, which was mistakenly listed as a sacred mushroom used in Mazatec rituals. It turns out that was a misidentification by an assistant on Wasson’s original expedition, so even in places where we thought Panaeolus was part of the tradition, the data fell through.

With all that said, Panaeolus affinis is occasionally cited in older ethnobotanical records as having been used for its psychoactive effects, but the context is thin and not tied to any specific cultural lineage.

So while Panaeolus cyanescens may not have the same documented ritual use as Psilocybe, that doesn’t mean it wasn’t part of the story. If we look at how Panaeolus is used and viewed today, especially compared to cubensis, it seems likely it was just as valued, if not more so. With Panaeolus species being smaller, less widespread, and harder to cultivate, they may have simply been more difficult to access. Personally, I think cubensis may have been used more commonly in group ceremonies, while Panaeolus held a quieter role in more selective or intentional settings.

Panaeolus Research and Studies

While most clinical studies today focus on Psilocybe cubensis or synthetic psilocybin, the same core compounds – psilocybin, psilocin, and baeocystin – are also present in Panaeolus cyanescens. That means research on psilocybin in general still offers important insight when studying Pan cyans.

Panaeolus Specific Research

Most of the published studies on P. cyanescens fall into a few main areas:

- Alkaloid Profiling

Researchers have measured levels of psilocybin, psilocin, and trace tryptamines across different samples and regions. P. cyanescens consistently ranks among the most potent species, sometimes surpassing 2% total alkaloids by dry weight. - Genetic Analysis

DNA sequencing has helped clarify its placement within the Panaeolus genus and explore its relationship to other psychoactive fungi. Some studies have looked at strain-level variation, though there’s still a lot we don’t know. - Comparative Studies

Several papers compare Pan cyans to more commonly cultivated species like Psilocybe cubensis, noting differences in potency, morphology, and cultivation behavior. - Pharmacological Research

One study explored the effects of P. cyanescens alkaloids on human cardiomyocytes (heart cells), looking at potential cellular impacts at the pharmacological level. While more research is needed, the study didn’t show harmful effects at typical exposure levels.

Psilocybin Focused Research

- Neuroplasticity and Brain Connectivity

Psilocybin has been shown to increase connectivity between brain regions, helping “reset” rigid thought patterns and promote new neural pathways. A study published in Nature demonstrated that psilocybin significantly disrupted functional connectivity in the brain, potentially enhancing its plasticity. - Treatment-Resistant Depression

Clinical trials have shown that psilocybin can produce long-lasting reductions in depression and anxiety after just one or two sessions. A phase 2 clinical trial reported significant improvements in patients with treatment-resistant depression following a single dose of psilocybin.

- Anti-Inflammatory Effects

Emerging research suggests that psilocybin may reduce inflammation by interacting with serotonin receptors involved in immune regulation. A study found that hot-water extracts of psilocybin-containing mushrooms exhibited potential anti-inflammatory effects in vitro.

- Visual and Sensory Perception

Low to moderate doses of psilocybin can heighten visual acuity, pattern recognition, and sensory processing, which may explain the vivid effects many people report. Research has investigated the neural mechanisms of psychedelic-induced visual imagery, providing insights into how psilocybin affects visual perception.

How to Grow Panaeolus cyanescens

While Panaeolus cyanescens grows abundantly in nature, it can also be cultivated at home. They’re more challenging than cubensis but most would agree, the reward is worth the effort.

General Requirements

To encourage fruiting, it helps to recreate the kind of environment they thrive in naturally:

Substrate: They prefer a mix of grass and dung-based substrates. Any grain used for cubes works fine for colonization, although they do best on grain that doesn’t retain a lot of moisture such as milo and millet.

Temperature: Colonization and fruiting tends to do best in the 75–85°F (24–29°C) range, although 77–83°F (25–28°C) is the sweet spot.

Relative Humidity: Since RH scales with temperature, it’s best to keep a range in mind and not a fixed number. While most sources recommend 95% or higher, I’ve found keeping it a bit lower helps prevent excess condensation, pooling, and water damage. I try to keep temps as close to 80° as possible and RH between 86%-90%.

Here is the sweet spot scale:

75-76°F (24.0-24.5°C) | RH 92-93%

77-78°F (25.0-25.5°C) | RH 90-91%

79-80°F (26.0-26.5°C) | RH 88-89%

81-82°F (27.0-28.0°C) | RH 86-87%

83-84°F (28.5-29.0°C) | RH 84-85%

Fresh Air: Consistent air circulation is really important when growing Panaeolus. In nature, they’re exposed to unlimited fresh air and frequent gentle breezes that naturally sweep CO₂ away. That’s exactly what you want to recreate in your fruiting environment. If you’re using small fans, keeping one on 24/7 can be really helpful (just make sure it’s not pointed at your trays and drying the sub out). If you’re using an exhaust fan, shorter, more frequent cycles tend to work best.

Casing Layer: Unlike cubes, Pans typically need a non-nutritive, casing layer to trigger pinning. A mix of sphagnum peat moss, vermiculite, and enough pickling lime or calcium carbonate to bring the pH to 7.5-8, works great to maintain surface moisture and encourage pin development.

pH Level: While not essential, maintaining a pH between 7.5 and 8 in both the substrate and casing helps reduce the risk of contamination. It doesn’t prevent it altogether, but it does slow things down enough to give mycelium a leading edge.

Beneficial Bacteria: Adding beneficial bacteria like Bacillus to your substrate can significantly reduce contamination, especially mold like Trichoderma. While it’s not commonly used by hobby cultivators, it’s a standard practice in large-scale mushroom farms, as well as in cannabis and crop production.

Field Capacity: While most grow teks suggest field capacity for Pans should be slightly wetter than for cubes, I’ve found the opposite to be true. I recommend keeping the substrate on the drier side (damp but not dripping when squeezed), until it’s fully colonized. Once colonized and cased, then you can give it a good drink of water before moving it into fruiting conditions. This helps prevent bacterial growth.

Conclusion

The more you work with Panaeolus cyanescens, the more it tends to challenge your assumptions and shift your perspective. It’s not just potent, it’s particular, and if you’re paying attention, it has a lot to teach.

Here are a few key takeaways:

- Panaeolus cyanescens is one of the most potent psychoactive mushrooms, often far stronger than Psilocybe cubensis.

- While Copelandia cyanescens is still widely used, the correct scientific name is Panaeolus cyanescens.

- Identification is based on its slender form, jet-black spore print, dung-based habitat, and intense blue bruising.

- It contains both psilocybin and high levels of psilocin, which contribute to its fast onset and intensity.

- It has a pantropical and subtropical distribution, commonly appearing in warm, humid pastures after rainfall.

- It’s actively studied in mycology and pharmacology, and while it can be cultivated, it’s more particular than other species and requires a mindful approach.

- While not as well documented in traditional ceremonies as Psilocybe species, that doesn’t mean Panaeolus cyanescens wasn’t part of the story. It may have just played a quieter role in more selective or intentional settings.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Is Copelandia cyanescens the same as Panaeolus cyanescens?

A: Yes. They’re the same species. Panaeolus cyanescens is the current scientific name, while Copelandia cyanescens is an older synonym that’s still commonly used in online forums, books and field guides.

Q: How strong are Pan Cyans?

A: Much stronger than your average cubensis. Lab tests and anecdotal reports consistently show they contain 2-3 times more active compounds by dry weight, so dosage should be adjusted accordingly.

Q: Where do Panaeolus cyanescens grow?

A: They grow primarily on herbivore dung (especially from cows and water buffalo), in warm, humid regions. You’ll typically find them in tropical and subtropical pastures and grazing fields after rainfall.

Q: Are Panaeolus cyanescens legal?

A: Legal status varies by location. Because they contain psilocybin and psilocin, they’re illegal in many parts of the world so make sure to check your local laws before possession or study.

Q: Why are Pan Cyans harder to grow than Cubensis?

A: Growing Panaeolus cyanescens isn’t necessarily more difficult, it’s more about precision. They thrive within specific environmental conditions, which typically takes a bit of initial setup to get right. But once you understand their preferences and have things dialed in, you’ll see they’re actually pretty easy to grow. Most people find the extra attention to detail is well worth the effort too. 😊

Q: How can you tell Panaeolus cyanescens apart from Psilocybe cubensis?

A: While the two share some traits, there are a few clear differences that make identification pretty straightforward. P. cubensis are typically larger, with thicker stems and more robust caps. P. cyanescens are smaller, more delicate, and have a graceful appearance.

If you’re unsure, spore color is one of the easiest ways to tell them apart. Pan cyans have jet-black spores, while cubensis spores are more purple-brown. You’ll also notice that P. cyanescens bruise a deeper, more vibrant blue and are most often found growing on dung, whereas cubensis prefer decaying plant matter and compost.

Q: Why does Panaeolus cyanescens bruise blue?

A: The blue bruising happens when psilocin, one of the mushroom’s main active compounds, oxidizes after being exposed to air. While bruising confirms the presence of psilocin, the intensity doesn’t always correlate with the overall potency. Factors like age, genetics, and environmental conditions play a role in how strong the bluing appears.

Q: Is it safe to microdose with Pan Cyans?

A: Many people find that P. cyanescens are great for daytime microdosing when focus, clarity and productivity are the goal, while cubes tend to be better suited for the evening when you’re ready to relax. Just keep in mind that P. cyanescens are extremely potent, so you’ll need far less by weight than you would with P. cubensis. It’s also important to note that individual experiences can vary quite a bit so it’s best to start low and see how you respond.

References

- Saccardo, P.A. (1887). Panaeolus cyanescens first described in Sylloge Fungorum. Read more on Wikipedia

- Singer, R. (1951). Reclassified Copelandia cyanescens as Panaeolus cyanescens, formalizing the taxonomic update based on morphology. View GBIF entry

- Wikipedia: Copelandia. Overview of the historical classification and reclassification of blue-staining Panaeolus species. Read more on Wikipedia

- Guzmán-Dávalos, L., Díaz-Barriga, A., Mora-Melgarejo, R., et al. (2018). The neurotropic genus Copelandia (Basidiomycota) in western Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 89(1), 1–12. Read article

- Lee, J., Cole, M., & Linacre, A. (2000). Identification of members of the genera Panaeolus and Psilocybe by a DNA test. Forensic Science International, 112(2–3), 123–133. Developed a DNA-based method using ITS sequences to distinguish between hallucinogenic mushroom genera.

Read article - Nkadimeng, S.M., Steinmann, C.M.L., & Eloff, J.N. (2020). Effects and safety of Psilocybe cubensis and Panaeolus cyanescens magic mushroom extracts on endothelin-1-induced hypertrophy and cell injury in cardiomyocytes. Scientific Reports, 10, Article 22314. Investigated the cardioprotective effects of magic mushroom extracts against induced hypertrophy and cell injury.

Read article - Siegel, J.S., Subramanian, S., Perry, D., et al. (2024). Psilocybin desynchronizes the human brain. Nature, 632, 131–138. Demonstrated that psilocybin disrupts functional connectivity in the brain, correlating with altered states of consciousness.

Read article - Goodwin, G.M., Aaronson, S.T., Alvarez, O., et al. (2022). Single-dose psilocybin for a treatment-resistant episode of major depression. The New England Journal of Medicine, 387(18), 1637–1648. Reported that a single dose of psilocybin produced rapid and sustained antidepressant effects in patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Read article

- Nkadimeng, S.M., Steinmann, C.M.L., & Eloff, J.N. (2021). Anti-inflammatory effects of four psilocybin-containing magic mushroom water extracts in vitro on 15-lipoxygenase activity and on lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 and inflammatory cytokines. Journal of Inflammation Research, 14, 3729–3738. Found that hot-water extracts of psilocybin-containing mushrooms exhibit potential anti-inflammatory properties by downregulating pro-inflammatory mediators.

Read article - Stoliker, D., Preller, K.H., Novelli, L., et al. (2025). Neural mechanisms of psychedelic visual imagery. Molecular Psychiatry, 30, 1259–1266. Explored how psilocybin alters visual processing in the brain, leading to enhanced visual imagery during psychedelic experiences.

Read article